Fully functional immune organ grown in mice from lab-created cells

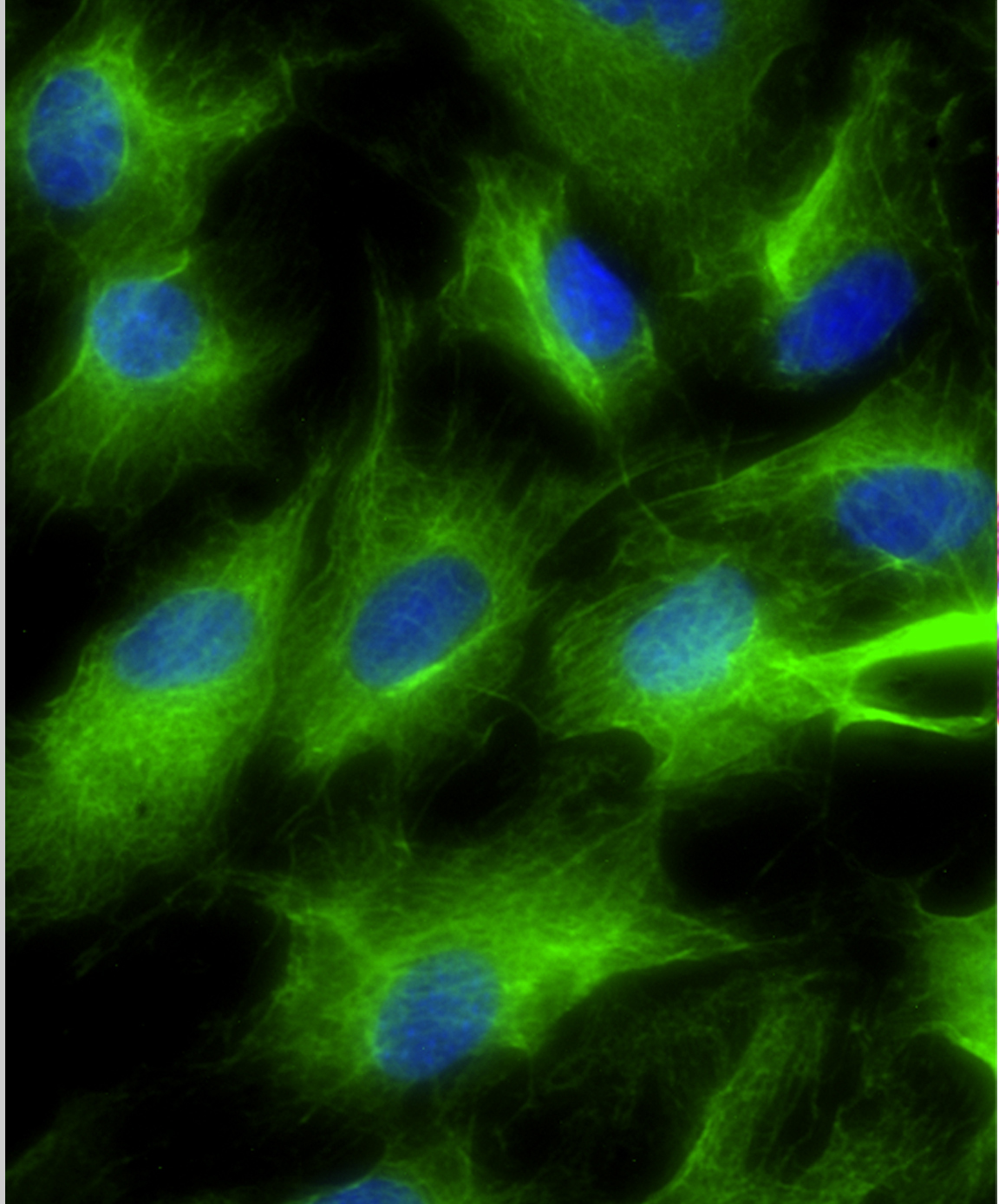

Image: Nick Bredenkamp

Medical Research Council Press Release

Scientists have for the first time grown a complex, fully functional organ from scratch in a living animal by transplanting cells that were originally created in a laboratory. The advance could in future aid the development of ‘lab-grown’ replacement organs.

Researchers from the MRC Centre for Regenerative Medicine, at the University of Edinburgh, took cells called fibroblasts from a mouse embryo and converted them directly into a completely unrelated type of cell - specialised thymus cells- using a technique called ‘reprogramming’. When mixed with other thymus cell types and transplanted into mice, these cells formed a replacement organ that had the same structure, complexity and function as a healthy native adult thymus. The reprogrammed cells were also capable of producing T cells - a type of white blood cell important for fighting infection - in the lab.

The researchers hope that with further refinement their lab-made cells could form the basis of a readily available thymus transplant treatment for people with a weakened immune system. They may also enable the production of patient-matched T cells. The research is published today in the journal Nature Cell Biology.

The thymus, located near the heart, is a vital organ of the immune system. It produces T cells, which guard against disease by scanning the body for malfunctioning cells and infections. When they detect a problem, they mount a coordinated immune response that tries to eliminate harmful cells, such as cancer, or pathogens like bacteria and viruses.

People without a fully functioning thymus can’t make enough T cells and as a result are very vulnerable to infections. This includes some patients who need a bone marrow transplant (for example in leukaemia), as a functioning thymus is needed to rebuild the immune system once the transplant has been received. The problem can also affect children; around one in 4,000 babies born each year in the UK have a malfunctioning or completely absent thymus (due to conditions such as DiGeorge syndrome).

Thymus disorders can sometimes be treated with infusions of extra immune cells, or transplantation of a thymus organ soon after birth, but both are limited by a lack of donors and problems matching tissue to the recipient.

Being able to create a complete transplantable thymus from cells in a lab would be a huge step forward in treating such conditions. And while several studies have shown it is possible to produce collections of distinct cell types in a dish, such as heart or liver cells, scientists haven’t yet been able to grow a fully intact organ from cells created outside the body.

Professor Clare Blackburn from the MRC Centre for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Edinburgh, who led the research, said:

“The ability to grow replacement organs from cells in the lab is one of the ‘holy grails’ in regenerative medicine. But the size and complexity of lab-grown organs has so far been limited. By directly reprogramming cells we’ve managed to produce an artificial cell type that, when transplanted, can form a fully organised and functional organ. This is an important first step towards the goal of generating a clinically useful artificial thymus in the lab.”

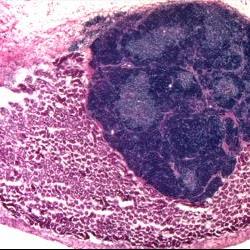

Image: Nick Bredenkamp

The researchers carried out their study using cells (fibroblasts) taken from mouse embryos. By increasing levels of a protein called FOXN1, which guides development of the thymus during normal organ development in the embryo, they were able to directly reprogramme these cells to become a type of thymus cell called thymic epithelial cells. These are the cells that provide the specialist functions of the thymus, enabling it to make T cells.

The induced thymic epithelial cells (or iTEC) were then combined with other thymus cells (to support their development) and grafted onto the kidneys of genetically identical mice. After four weeks, the cells had produced well-formed organs with the same structure as a healthy thymus, with clearly defined regions (known as the cortex and medulla). The iTEC cells were also able to produce different types of T cells from immature blood cells in the lab.

Dr Rob Buckle, Head of Regenerative Medicine at the MRC, said:

“Growing ‘replacement parts’ for damaged tissue could remove the need to transplant whole organs from one person to another, which has many drawbacks – not least a critical lack of donors. This research is an exciting early step towards that goal, and a convincing demonstration of the potential power of direct reprogramming technology, by which once cell type is converted to another. However, much more work will be needed before this process can be reproduced in the lab environment, and in a safe and tightly controlled way suitable for use in humans.”

The study was funded by Leukaemia and Lymphoma Research, Darwin Trust of Edinburgh, the MRC and the European Union Seventh Framework Programme.

Further information

- A video showing the artificial thymus can be seen here.

- To request an interview with the authors or for further information please contact the MRC press office on 0207 395 2345 (out of hours: 07818 428 297) or email press.office@headoffice.mrc.ac.uk.

Last updated: